Redefining Working Class: What is Working Classness?

Are we truly just lazy?

Headlines usually look at working-class people and advertise them as people who don’t work hard, want benefits and free money given to them, live in free housing and get involved in crime and other antisocial behaviour to waste away their days.

However, my reality has been completely different. I was born into a working-class family with a strive to work hard, push to create a home and be a respectful citizens who would go up the social ladder through the right means. And so my parents worked hard to move away from the council housing that we were in and into a house that they worked hard for and saved a load of money to be able to afford the deposit, to then go on to pay a mortgage with left them barely anything to spend money on ‘luxuries’ like holidays or new items for the house. Instead, it went towards repairing their home, making sure that they could survive and pay for food, heating and electricity.

And my family’s story is not an exception. There are many other families that go through this struggle. But, when we hear working class, the majority of us go straight to the top description, not the bottom one. Why? Because it is always easier to just demonise the working class than to help or to show the reality of what they have to go through.

I mean it is clearly evident that when working classness is portrayed in a different light, people are outraged as the work doesn’t have a ‘sufficiently positive attitude’ which is something that we are striving to change. As much as I love reading the Guardian, the review on the exhibition truly did not comprehend what the space tried to do. And I will write more on this next week.

The demonising of the working class

The book Chavs came over a decade ago. However, it could not be any more relevant to today’s society, only to show that there has been no real progress made in our society to understand the class divide or what it means to be working class.

The book rightly expresses how the working class are portrayed in politics and the media as I have briefly expressed in my previous article and will do in my final article. But what is more interesting is the way in which classness has been something that, by name, is being removed to suggest that there is no discrimination and that we all have equal opportunity to ‘make it’ (meritocracy) and that it is up to the individual to make what they can with the resources, only to remove responsibility off of the state or organisations and back to the individual.

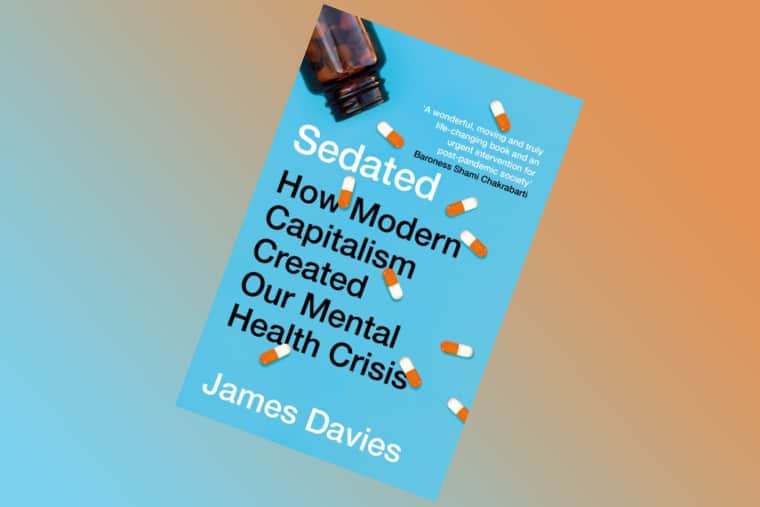

Now, that doesn’t mean that the state stops helping individuals. No. They are helping by providing services to the working class, like the Job Centre or with other health and social care provisions. However, as James Davies exposes in his book Sedated, the system has many holes which do the opposite of helping, only making individuals more ill or being unhelpful to their journey to recovery or work.

Yet the media focus on the fact that there is so many ‘resources’ yet working class individuals are being ‘lazy’, taking ‘advantage’ of the services that they are ‘paying for’ to just ‘sit comfortably’ when the reality is far from this tinted view that they have to what it means to be working class.

By providing these ‘provisions’ only goes to make the individual responsible of the circumstances that they have to live in and if you are unable to survive, you continue to be negatively viewed due to the inability to survive in this capitalist, competitive society we live in today.

This is something that both Jones and Davies speak about in their books as being one of the issues as this view makes working class individuals seem as they are unworthy of help in progressing and continues to strengthen the view that the media and political groups want to amplify to create a common enemy: the working class people.

The combination of the working class with ethnic and racial groups

Ethnic migrants have always faced aggression; however, this is something that has amplified as we have seen the rise in terror acts, the far rights gain more traction in the UK and globally too. This anti-migrant rhetoric continues to be thrown around without knowing who and what the real problem is. And the delay in publishing this data continues to cause social uproar.

In reality, the general services we use would not function without these migrants working and picking up jobs that we either don’t have the skills to do or are purely unwilling to do.

Thus, when we are talking about working-class people, it is important to also include migrants who start mostly at the bottom of the ladder and try to strive upwards due to the promised idea of ‘meritocracy’- the equal opportunity to grow so long as you work hard. They are not all lazy and unwilling to work, but they have to go through the struggles to then be able to uplift themselves from the ground and make their mark. It is a common migrant child journey in which children of migrants usually work hard and try to strive for the best due to the need to make the struggles of their parents worth it and help them move up the ladder together.

And this is similar to my case. As the first child of two immigrants, it was embedded in me that I had to get good grades, be ahead and work twice as hard to meet what my white counterparts had. Now in my twenties, I have certain realisations as to how accurate this is in terms of social capital and cultural capital that I play catch up with for me to fit in with my peers.

Therefore, the narrative that they are here to ‘steal our jobs’ or the idea of there being ‘no space’ or even the idea that they are ‘abusing the system’ seems to be an idea that has continually spread to continue to amplify hate, anger and frustration within the working class to divide them rather than stand together for their needs and wants.

General Consensus

As you will see in this piece and the following pieces, there is a need for working-class people to take back control over the narratives that have been shared to give them back their rightful identity to wear with pride.

The media and politics have often vilified the working class and made them separate from the general population, however, it is now an opportunity to change these negative discourses surrounding working classness and provide our communities and societies with an alternative, more humanised version of the experiences that individuals experience.